Memory management in Swift with ARC

Memory management in general

There are two main approaches to memory management:

- Manual memory management. This type of memory management is frequently used in systems where performance matters and additional overhead for automatic memory management at runtime is not allowed. In this case, a programmer is responsible for manually allocating and freeing memory.

- Automatic memory management. Manual memory management is error prone because in complex codebases it is very easy to forget to free allocated memory or accidentally use already freed memory. For this reason, some programming languages have built-in mechanisms for automatic memory management. The most popular one is the garbage collector. A garbage collector is just a chunk of code integrated with your binary that frees memory at some time during execution (the details of when the garbage collector frees memory can depend on implementation details). In this case, a programmer just deals with program logic and does not distract from memory management because the garbage collector does it implicitly. But most implementations of garbage collectors free memory at a time when memory pressure happens and it leads to additional overhead during program execution.

Automatic Reference Counter

Automatic Reference Counter or just ARC is Apple’s approach to dealing with memory management. Before ARC was introduced in Objective-C programmers were using a method called manual retain-release or MRR to explicitly manage the memory of applications by specifying when an object must be retained and when it must be released. The method is based on reference counting but the problem is that a programmer must specify a proper calling of retain/release methods that were working in a pair. ARC is the compiler feature that is responsible for injecting retain/release methods in a code implicitly instead of a programmer. But now programmers have another responsibility - build proper relationships between objects to avoid retain cycles when objects retain each other which leads to memory leaks. So let’s see ARC in action with a few common examples of retain cycles and how to help ARC break those retain cycles with Swift language features.

ARC in action

Suppose we have the next class:

class Employee {

let name: String

init(name: String) {

self.name = name

}

deinit {

print("\(#function): \(name)")

}

}In the Employee class we declared the deinit method with print() function inside to see that the instance of that class is released.

Now we create a few instances of the Employee class and check the output of execution:

var t1: Employee?

var t2: Employee?

var t3: Employee?

t1 = Employee(name: "John Doe")

t2 = t1

t3 = t1

t1 = nil

t2 = nil

t3 = nil

#=> prints 'deinit: John Doe'Here we create three instances of the Employee? class, then assign the t1 variable a value. Next, for t2 and t3 we also assign the value from the t1 variable. Now t1, t2, and t3 variables refer to the same instance in the memory. When we assign t1 and t2 variables nil nothing happens because the Employee instance is still retained by the t3 variable. After assigning nil to the t3 variable we can see deinit: John Doe in the output which indicates that the Employee instance was released as expected.

An example with a situation where two properties, both of which are allowed to be nil, have a strong reference cycle

Let’s take a look at an example where two properties, both of which are allowed to be nil, have a strong reference cycle.

Suppose we have two classes with properties that refer to an instance of each other:

class Pilot {

let name: String

var f1Car: F1Car?

init(name: String) {

self.name = name

}

deinit {

print("\(#function): \(name)")

}

}

class F1Car {

let model: String

var pilot: Pilot?

init(model: String) {

self.model = model

}

deinit {

print("\(#function): \(model)")

}

}When we create instances of those classes we can indicate that the retain cycle occurred because deinit is not called for any of those instances:

let pilot = Pilot(name: "Alonso")

let f1Car = F1Car(model: "R2022")

pilot.f1Car = f1Car

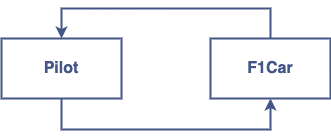

f1Car.pilot = pilotTo figure out what happened let’s draw a diagram:

As you can see on the diagram the instances hold a strong reference to each other which leads to a memory leak because the reference counter is not zero for both instances and ARC does not mark the instances as ready to release to free memory in the future. There are a few possible options to break the retain cycle. Let’s see them in action.

Resolve the retain cycle with weak property

The most popular option to resolve a retain cycles for this scenario. All you need to do is to mark a property as weak. Which property must be marked as weak depends on the relationships between objects in a system. In our example suppose that the Pilot class is more important than the F1Car class so the Pilot instance owns an instance of the F1Car and holds a strong reference. On the other hand, the F1Car instance does not own an instance of the Pilot so we can mark its pilot property as weak. Rewrite the F1Car class as below:

class F1Car {

let model: String

weak var pilot: Pilot?

init(model: String) {

self.model = model

}

deinit {

print("\(#function): \(model)")

}

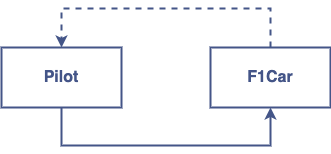

}Now our diagram looks a little bit different:

When we run the client’s code again we can see that both deinit methods are called:

let pilot = Pilot(name: "Alonso")

let f1Car = F1Car(model: "R2022")

pilot.f1Car = f1Car

f1Car.pilot = pilot

#=> prints 'deinit: Alonso'

#=> prints 'deinit: R2022'An example with a situation where one property that’s allowed to be nil and another property that can’t be nil have the potential to cause a strong reference cycle

Let’s look at a situation where one property that’s allowed to be nil and another property that can’t be nil have the potential to cause a strong reference cycle. In this scenario, we can break the potential retain cycle by specifying a property which refers to an object whose lifetime is the same or greater as unowned.

Here is the code:

class Pilot {

let name: String

var f1Car: F1Car?

init(name: String) {

self.name = name

}

deinit {

print("\(#function): \(name)")

}

}

class F1Car {

let model: String

unowned var pilot: Pilot

init(model: String, pilot: Pilot) {

self.model = model

self.pilot = pilot

}

deinit {

print("\(#function): \(model)")

}

}

let pilot = Pilot(name: "Alonso")

let f1Car = F1Car(model: "R2022", pilot: pilot)

pilot.f1Car = f1Car

#=> prints 'deinit: Alonso'

#=> prints 'deinit: R2022'An example in which both properties should always have a value, and neither property should ever be nil once initialization is complete

Yet another situation where both properties should always have a value and neither of them should ever be nil once initialization is complete. In this scenario, it’s useful to combine an unowned property on one class with an implicitly unwrapped optional property on another class. Let’s take a look at an example:

class Pilot {

let name: String

var f1Car: F1Car!

init(name: String, f1CarModel: String) {

self.name = name

self.f1Car = F1Car(model: f1CarModel, pilot: self)

}

deinit {

print("\(#function): \(name)")

}

func info() {

print("\(name) drives \(f1Car.model)")

}

}

class F1Car {

let model: String

unowned var pilot: Pilot

init(model: String, pilot: Pilot) {

self.model = model

self.pilot = pilot

}

deinit {

print("\(#function): \(model)")

}

func info() {

print("\(model) is driven by \(pilot.name)")

}

}In the example above the F1Car has the unowned reference to the Pilot instance and it’s OK because the Pilot instance has a lifetime equal to or greater than the F1Car instance. At the same time, the Pilot class has forced unwrapped reference to the F1Car instance but as the F1Car instance is initialized during the Pilot initialization we are confident that the F1Car instance can’t be nil.

The client’s code:

let pilot = Pilot(name: "Alonso", f1CarModel: "R2022")

pilot.info()

pilot.f1Car.info()

#=> prints 'Alonso drives R2022'

#=> prints 'R2022 is driven by Alonso'

#=> prints 'deinit: Alonso'

#=> prints 'deinit: R2022'Redesigning a system to resolve the retain cycle

Also, we can resolve the retain cycle by redesigning relationships between objects by adding new types which help to avoid the usage of weak or unowned specifiers in the main types of a system. It gives us more flexibility but also we need to write more code. Let’s see a few examples.

Resolve the retain cycle by redesigning the system by adding a new type to avoid using weak or unowned

The first way to break the retain cycle is by redesigning the system by adding a new type and avoiding the usage of weak or unowned specifiers completely. Let’s see an example:

class Pilot {

let name: String

var f1CarInfo: F1CarInfo?

init(name: String) {

self.name = name

}

deinit {

print("\(#function) (\(Pilot.self): \(name)")

}

func info() -> String {

"\(name) drives \(f1CarInfo?.model ?? "none")"

}

}

class F1CarInfo {

let model: String

init(model: String) {

self.model = model

}

deinit {

print("\(#function) (\(F1CarInfo.self)): \(model)")

}

}

class F1Car {

let carInfo: F1CarInfo

var pilot: Pilot?

init(carInfo: F1CarInfo) {

self.carInfo = carInfo

}

deinit {

print("\(#function) (\(F1Car.self)): \(carInfo.model)")

}

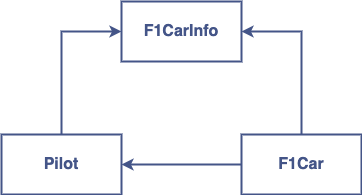

}The relationship between the objects looks like this:

As you can see in this system the main entity is the F1Car which holds a strong reference to the Pilot. The Pilot also needs to know some information about the F1Car and for that, we extract this information to the additional type F1CarInfo which is shared between the Pilot and the F1Car. This scheme also allows us to break the possible retain cycle between the Pilot and F1Car.

And here is the client’s code:

let f1CarInfo = F1CarInfo(model: "R2022")

let f1Car = F1Car(carInfo: f1CarInfo)

let pilot = Pilot(name: "Alonso")

pilot.f1CarInfo = f1CarInfo

f1Car.pilot = pilot

print(pilot.info())

#=> prints 'Alonso drives R2022'

#=> prints 'deinit (F1Car): R2022'

#=> prints 'deinit (Pilot: Alonso'

#=> prints 'deinit (F1CarInfo): R2022'Resolve the retain cycle by using the Weak Reference pattern

And one more approach to breaking the retain cycle is the Weak Reference pattern which is quite similar to the previous approach except that in this case, we use a generic type that can be extended to satisfy relationships between objects. So, let’s take a look at an example:

protocol F1CarProtocol {

var model: String { get }

}

class WeakReference<T: AnyObject> {

private weak var object: T?

init(_ object: T) {

self.object = object

}

deinit {

print("\(#function) (\(WeakReference.self)): \(String(describing: object.self))")

}

}

extension WeakReference: F1CarProtocol where T: F1CarProtocol {

var model: String {

get {

object?.model ?? "none"

}

}

}

class Pilot {

let name: String

var f1Car: F1CarProtocol?

init(name: String) {

self.name = name

}

deinit {

print("\(#function) (\(Pilot.self)): \(name)")

}

func info() {

print("\(name) drives the \(f1Car?.model ?? "none")")

}

}

class F1Car: F1CarProtocol {

let model: String

var pilot: Pilot?

init(model: String) {

self.model = model

}

deinit {

print("\(#function) (\(F1Car.self)): \(model)")

}

func info() {

print("\(model) is driven by \(pilot?.name ?? "none")")

}

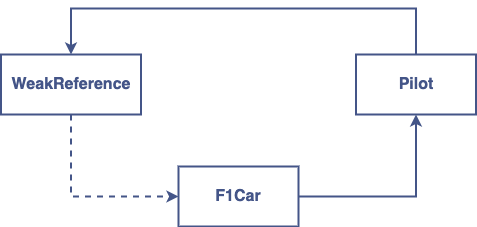

}As you can see from the code above the WeakReference generic class is responsible for holding a weak reference to a specified object and can be used as an additional type in a system to break the retain cycle.

The client’s code looks like this:

let pilot = Pilot(name: "Alonso")

let f1Car = F1Car(model: "R2022")

let f1CarWeakReference = WeakReference(f1Car)

pilot.f1Car = f1CarWeakReference

f1Car.pilot = pilot

f1Car.info()

pilot.info()

#=> prints 'R2022 is driven by Alonso'

#=> prints 'Alonso drives the R2022'

#=> prints 'deinit (F1Car): R2022'

#=> prints 'deinit (Pilot): Alonso'

#=> prints 'deinit (WeakReference<F1Car>): nil'Here is the relationship between objects:

Conclusion about a system redesign

The main goal of redesigning a system is hiding from entities knowledge about their relationships (who must hold a weak reference and who must hold a strong reference etc). Also, it corresponds to the open-closed principle because we do not need to change relationships between objects by specifying weak or unowned references. All we need to do is to extend the system with instances of the WeakReference type or another.

Retain cycles for closures

And one more frequent way to accidentally make a retain cycle is strong references between a class instance and a closure. For example:

class Button {

var onTapAction: (() -> Void)?

init() {

onTapAction = {

self.info()

}

}

deinit {

print("\(#function): \(Button.self)")

}

func info() {

print("\(#function): \(Button.self)")

}

}In the example above the Button instance has a strong reference to the onTapAction which is a closure. In the init method we create an instance of type () -> Void and assign it to the onTapAction. In the body of the closure which is assigned to the onTapAction property we also have a strong reference to self which leads to a retain cycle. As we know closures are reference types so the same rules as for classes are applied to closures too. The simplest way to break the retain cycle is to capture self as a weak reference:

init() {

onTapAction = { [weak self] in

self?.info()

}

}This way we can break the retain cycle.

Experimental ARC optimization

Also need to mention that since Xcode 13 a new experimental compiler optimization Optimize Object Lifetimes is available. As Apple says:

With this build setting turned on, you may see objects being deallocated immediately after last use much more consistently, bringing observed object lifetimes closer to their guaranteed minimum.

Resources:

Another way to deal with manual memory management with withExtendedLifetime(_:_:) function